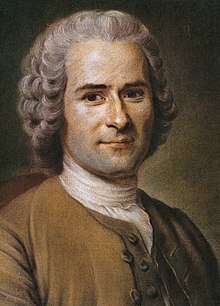

The thinking

of Swiss philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who was born on June 28, 1712,

influenced the French Revolution. It

also inspired Walter Scott’s friend Lord Byron.

Sir Walter Scott provides evidence, and his own opinions, in his biographical

sketch of Lord Byron, which is published in “The Miscellaneous Works of Sir

Walter Scott”.

‘…The next theme on which the poet [Byron] rushes, is the

character of the enthusiastic, and as Lord Byron well terms him,

"self-torturing sophist, wild Rousseau,"

a subject naturally suggested by the scenes in which that unhappy visionary

dwelt, at war with all others, and by no means at peace with himself; an

affected contemner of polished society, for whose applause he secretly panted,

and a waster of eloquence in praise of the savage state in which his

paradoxical reasoning, and studied, if not affected, declamation, would never

have procured him an instant's notice. In the following stanza, his character

and foibles are happily treated.

"His life was one

long war with self-sought foes, Or friends by him self-banish'd; for his mind

Had grown Suspicion's sanctuary, and chose For its own cruel sacrifice, the

kind, 'Gainst whom he raged with fury strange and blind. But he was

frenzied—wherefore, who may know? Since cause might be which skill could never

find; But he was frenzied by disease or woe, To that worst pitch of all, which

wears a reasoning show."

In another part of the

poem, this subject is renewed, where the traveller visits the scenery of La

Nouvelle Eloise.

"Clarens, sweet Clarens, birthplace of deep love,

Thine air is the young breath of passionate thought;

Thy trees take root in love; the snows above

The very Glaciers have his colours caught,

And sunset into rose-hues sees them wrought,

By rays which sleep there lovingly."

Thine air is the young breath of passionate thought;

Thy trees take root in love; the snows above

The very Glaciers have his colours caught,

And sunset into rose-hues sees them wrought,

By rays which sleep there lovingly."

There is much more of beautiful and animated description, from which it appears that the impassioned

parts of Rousseau's romance have made a deep impression upon the feelings of

the noble poet. The enthusiasm expressed by Lord Byron is no small tribute to

the power possessed by Jean Jacques over the passions; and, to say truth, we

needed some such evidence, for, though almost ashamed to avow the truth, which

is probably very much to our own discredit, still, like the barber of Midas, we

must speak or die, we have never been able to feel the interest, or discover

the merit, of this far-famed performance. That there is much eloquence in the

letters, we readily admit: there lay Rousseau's strength. But his lovers, the

celebrated St Preux and Julie, have, from the earliest moment we have heard the

tale (which we well remember) down to the present hour, totally failed to

interest us. There might be some constitutional hardness of heart; but, like

Lance's pebblehearted cur, Crab, we remained dry-eyed, while all wept around

us. And still, on resuming the volume, even now, we can see little in the loves

of these two tiresome pedants to interest our feelings for either of them; we

are by no means flattered by the character of Lord Edward Bomston, produced as

the representative of the English nation; and, upon the whole, consider the

dulness of the story as the best apology for its exquisite immorality. To state

our opinion in language much better than our own, we are unfortunate enough to

regard this far-famed history of philosophical gallantry as an

"unfashioned, indelicate, sour, gloomy, ferocious medley of pedantry and

lewdness; of metaphysical speculations, blended with the coarsest

sensuality." Neither does Rousseau claim a

higher rank with us on account of that Pythian and frenetic inspiration which

vented

"Those oracles which set the world in flame,

Nor ceased to burn till kingdoms were no more."

Nor ceased to burn till kingdoms were no more."

We agree with Lord Byron that this frenzied sophist,

reasoning upon false principles, or rather presenting that show of reasoning

which is the worst pitch of madness, was a primary apostle of the French

Revolution; nor do we differ greatly from his Lordship's conclusion, that good

and evil were together overthrown in that volcanic explosion. But when Lord

Byron assures us, that after the successive changes of government by which the

French legislators have attempted to reach a theoretic perfection of constitution,

mankind must and will begin the same work anew, in order to do it better and

more effectually,—we devoutly hope the experiment, however hopeful, may not be renewed in our

time, and that the " fixed passion" which Childe Harold describes as

"holding his breath," and waiting the "atoning hour," will

choke in his purpose ere that hour arrives. Surely the voice of dear-bought

experience should now at length silence, even in France, the clamour of

empirical philosophy. Who would listen a moment to the blundering mechanic who

should say, " I have burned your house down ten times in the attempt, but

let me once more disturb your old fashioned chimneys and vents, in order to

make another trial, and I will pledge myself to succeed, in heating it upon the

newest and most approved principle?"…’

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.